First, a word about Louis Sachar's novel Holes. Yes, I realise it was written for those poor benighted sods they call 'young adults', but anyone who writes for a living needs to read it. Seriously, anyone. It is an unmarked tour de force of the sort of writing that makes text invisible. Sachar makes his points neither by planting signs all over them with arrows saying "LOOK! Here's the POINT! In case you MISSED it!" nor by shoehorning them into something that sometimes called subtext (which it isn't) ... but just by making them. Simply, and with the sort of directness that makes you feel like music is playing inside your head, rather than coming from the hifi in the corner. This is just so freakily rare that reading his prose is like aquaplaning in your car -- you're out of control, sliding frictionless over the tarmac, and it's almost disconcerting, so accustomed are we to the grind and drag of crappy, tortured mangling of language. And that's not even paying any attention to the brilliant, brilliant narrative control. But anyway.

The hero of Sachar's novel is a kid called Stanley, whose family has some problems his father attributes to his no-good dirty rotten pig-stealing great great grandfather, who among other things reneged on his promise to carry a certain Madame Zeroni up a mountain in return for advice on fattening his pig. (This is only a tiny fraction of the fractally fabulous plot). Stanley's father is trying to develop a cure for foot odor, but isn't making any headway. Clipped into the story like a tiny oiled cog in its intricate, silvery gears, is the fact that Stanley unknowingly meets Madame Zeroni's great great grandson, and carries him up a mountain. That day, Stanley's father hits on the cure for foot odor.

Two years ago, I flew home to visit my family in Australia, via Singapore. I had several hours to kill in the Singapore airport transit lounge, which is an enormous sprawling mop of pink carpeted causeways and departure lounges garnished with shops containing brightly coloured national dress and sparkling digital gadgetry and Swiss watches and sushi bars with plate glass frontages which gleam as though minions in blue-grey overalls polish them with chamoises every ten minutes. Wait, they do. Naturally, it is soul-suckingly vile beyond belief.

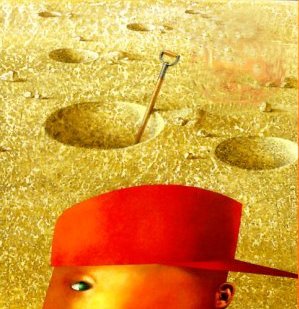

But that day, among the miniature copies of Singapore Airlines flight attendent cheong-sams, there was a calligrapher. He was wiry and leathery and had crinkly, hooded eyes, and spoke no English. He had a table, a pile of paper, some ink blocks and his brushes laid out on a wooden tray like surgical instruments. It was about 7AM, and there was no-one about. I watched him paint scrolls, and carefully lay them aside to dry. Sometimes, he would make a stroke he didn't like, and the sheet would be whipped from the table as from a typewriter, and dumped unceremoniously on the floor underneath the table. Of course, it was mesmerising. My favourite part was the moment he finished a scroll which pleased him, and he would take up his small square signature block, press it carefully into the red ink, and mark it to the paper as though tucking it into bed.

After a while, the shop attendent came over to see how he was doing, and offer him some tea. He spoke to her, and she turned to me. "He says, would you like to buy one?" Of course I did. I hated to think what they cost, but I'd been watching him an hour. I gestured at the drying scrolls, all different. "What do these mean?" I asked. I watched her translate for me, but he waved his arms impatiently before she was done. "He says, no, one for you. What do you do?" I told her that I was a student. "Of what?"

"Philosophy."

She didn't even blink. She turns to my Yoda-impersonator calligrapher. Out came the brushes and the new sheet of paper. First try ... no, he doesn't like it. Second sheet. Sweep, stroke, sweep. He puts the red signature block on to it and holds it out to me. "What does it mean?" She thinks carefully.

"Diligent thinking."

This is so bizarrely apposite that I'm silenced. And it's ludicrously cheap. They wrap it in cellophane for me and I put it into my suitcase and forget about it. For two years it's been shuttling around, under beds, in cupboards, down the side of the filing cabinet, under a pile of journal articles.

Last week, I finally got around to putting it into a dark-stained birch frame, and propping it over my desk. This week, I've written 7,500 words, lodged a job application and a writing sample to support another job application, read nine journal articles, ordered all the books I need for the next term, and revised an article for publication that ought to have been finished six months ago.

'Course, there could be lots of reasons. Maybe.

1 comment:

Oh my dog. HOLES is one the The Best Books I've Ever Read and yes we own a copy of it. Wouldn't it be cool if the 300 year old calligrapher had a mental link with his art and activated its special powers once the scroll has been appropriately honoured? I mean, spooky cool? Or maybe you're well rested enough to feel creative. I hope you get paid to write sometimes.

Post a Comment