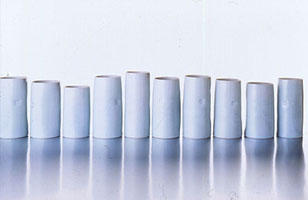

Edmund de Waal is a ceramic artist. He makes pots. At least, that's the way he describes it. He's also an academic of particularly fine standing who has written several books. As an aspiring academic, that impresses the hell out of me (not least because he's only 41) but really, I'm interested in the pots.

I'm a philosopher of science, nominally, and I don't know anything about art. At least, not in the sense that the people who comment on de Waal's books have in mind. Of course, that makes no difference to the pots, plates, drawings, linocuts, woodcuts, letterpress work, watercolours and glass which take hold of me and don't let go. But it does make it twice as exciting, for my sudden love of these things has both the thrill of the vertiginous plunge away from understanding, and the irresistible draw of the mysterious, like the fascination that attends watching two people converse in another language.

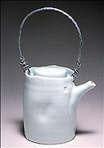

I found de Waal's work through one of my other mysterious loves: teapots. Actually, I don't think it's that mysterious, because I think teapots are plugged into our aesthetic DNA somehow. They are like one of the cultural tropes that appears everywhere, like quest myths. But I digress. I bought a catalogue from an exhibition called Time for Tea that the British Council staged for its collection of teapots. (I was persuaded by the Eric Ravilious woodcut on the cover). One of the pages features a pair of de Waal teapots. They were a soft green. The sort of thing that made me want to throw all my furniture into a skip, and have nothing in the house except the teapots on the mantelpiece under a single halogen spot.

Descriptions of de Waal's work always include the authenticity rider, that declamatory insistence on the most outre of ceramics that they are "intended for everyday use", as though this makes them somehow less pretentious, more real, more down-to-earth, somehow, than cups and pots and dishes intended just to be decorative. This has always puzzled me a little -- what is so wrong with something that is meant just to be beautiful? A thing which is pretentious is pretentious even if someone really serves tea in it or puts a flower in it. And a beautiful thing, a thing as gorgeous, as unpretentious and organic as de Waal's teapot, does not need to actually pour tea for me to long to hold it in my hands. But perhaps it is knowing that it might quite easily be enveloped in a cloud of hot jasmine-scented steam that makes it as beautiful as it is.

Descriptions of de Waal's work always include the authenticity rider, that declamatory insistence on the most outre of ceramics that they are "intended for everyday use", as though this makes them somehow less pretentious, more real, more down-to-earth, somehow, than cups and pots and dishes intended just to be decorative. This has always puzzled me a little -- what is so wrong with something that is meant just to be beautiful? A thing which is pretentious is pretentious even if someone really serves tea in it or puts a flower in it. And a beautiful thing, a thing as gorgeous, as unpretentious and organic as de Waal's teapot, does not need to actually pour tea for me to long to hold it in my hands. But perhaps it is knowing that it might quite easily be enveloped in a cloud of hot jasmine-scented steam that makes it as beautiful as it is. And of course, some part of me knows that no-one should put the teapot under a halogen spot. It would be twice as compelling crowded on a shelf with a few jugs and a vase, a nest of cups, a couple of walnuts in a Moroccan dish and a fading bunch of cornflowers, and perhaps a picture of your grandmother.

And of course, some part of me knows that no-one should put the teapot under a halogen spot. It would be twice as compelling crowded on a shelf with a few jugs and a vase, a nest of cups, a couple of walnuts in a Moroccan dish and a fading bunch of cornflowers, and perhaps a picture of your grandmother.

No comments:

Post a Comment