I hate a link that takes you to something that you have to register to see. Even worse, a link that takes you to something you have to

pay to see. How tantalisingly cruel is that? Even if you know that what's behind the iron-link-curtain is probably not worth the time it takes to think up some random password or other, the Not Knowing is just excruciating.

So pardon me for breaking all my own rules, by pointing you to

this article by Steve Almond at

Salon, which made me laugh out loud four times, which may be a record for anything I've read before 11AM on a Wednesday. You should

subscribe, anyway. I bet you think that there is more brilliant, free content on the internet for you to read in a lifetime, so there can be no possible reason for paying for some. Who am I to argue? But you're wrong.

My favourite part of Almond's article is this:

I find all book festivals depressing, because we writers are so disappointing in person, so awkward and needy and choked with status angst.

Egad. Just what I've always thought about conferences and academics. Of course, some academics are special, and are truly gripping in person. But I've come to think that is something which floats completely independently of being an academic. They had charisma, and meatspace-skills, before they ever lined their office with the latest issues of

Mind. Or, they didn't.

The way that the mythology of The Writer works means that although the cult of celebrity hounds them onto panels at literary festivals, ultimately they can argue that it doesn't make a shred of difference whether or not they themselves are even

interesting, much less whether they can fascinate people in person. The point is The Book, or (heaven help us) The Text.

That might be true.

But even if it

is true, I worry that something of this lurks in the minds of academics. If I can produce searing analytical prose from my dusty garret piled with dog-eared journal articles, slightly wilted pot plants and first editions of Wittgenstein, then

that's all that matters. I can be as awkward and obtuse in person as I like. I can go to a conference and

read my paper, badly, with my nose pressed closely into the pages, and fumble with my useless overheads crammed with twelve-point type. It's all in the

text. But it really, really isn't. Academics are not writers, even though writing is perhaps the flagship of their endeavours. Academics purvey ideas. They (brace yourselves)

teach. And I don't just mean apathetic undergraduates. I mean

everyone to whom the academic might like to convey her work. If your work is any good, then it should be the kind of thing that no-one has thought of before. And if that's true, then you have to teach it to people. You have to explain how it does what it does, and why it makes any difference. Anyone who thinks that their written work exhausts that responsibility is surely mistaken.

One of the most (perhaps even

the most) influential works in twentieth-century philosophy is

Kripke's Naming and Necessity. Kripke never even wrote it down. It was transcribed from a series of lectures he gave at Princeton in 1972. It's not hard to see how much this affects the genius of the book. Simple, declarative sentences and the cadence of a conversation you're having with someone who's very, very smart. Spare, pared-back everyday examples that the audience can hold in mind and which don't require Kripke to number his propositions and refer back to something-something-prime-star four pages ago. Something of the narrative lingers around the lectures, the draw and swell of beginning, middle and end that is so absent from the relentless and encyclopedic feel of much of the literature.

We would all love to steal a little of Kripke's genius, and we should start by remembering that most of it is

spoken.

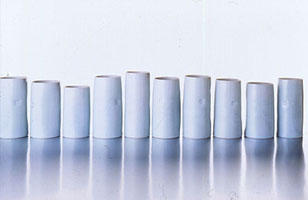

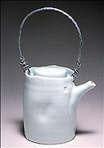

Descriptions of de Waal's work always include the authenticity rider, that declamatory insistence on the most outre of ceramics that they are "intended for everyday use", as though this makes them somehow less pretentious, more real, more down-to-earth, somehow, than cups and pots and dishes intended just to be decorative. This has always puzzled me a little -- what is so wrong with something that is meant just to be beautiful? A thing which is pretentious is pretentious even if someone really serves tea in it or puts a flower in it. And a beautiful thing, a thing as gorgeous, as unpretentious and organic as de Waal's teapot, does not need to actually pour tea for me to long to hold it in my hands. But perhaps it is knowing that it might quite easily be enveloped in a cloud of hot jasmine-scented steam that makes it as beautiful as it is.

Descriptions of de Waal's work always include the authenticity rider, that declamatory insistence on the most outre of ceramics that they are "intended for everyday use", as though this makes them somehow less pretentious, more real, more down-to-earth, somehow, than cups and pots and dishes intended just to be decorative. This has always puzzled me a little -- what is so wrong with something that is meant just to be beautiful? A thing which is pretentious is pretentious even if someone really serves tea in it or puts a flower in it. And a beautiful thing, a thing as gorgeous, as unpretentious and organic as de Waal's teapot, does not need to actually pour tea for me to long to hold it in my hands. But perhaps it is knowing that it might quite easily be enveloped in a cloud of hot jasmine-scented steam that makes it as beautiful as it is. And of course, some part of me knows that no-one should put the teapot under a halogen spot. It would be twice as compelling crowded on a shelf with a few jugs and a vase, a nest of cups, a couple of walnuts in a Moroccan dish and a fading bunch of cornflowers, and perhaps a picture of your grandmother.

And of course, some part of me knows that no-one should put the teapot under a halogen spot. It would be twice as compelling crowded on a shelf with a few jugs and a vase, a nest of cups, a couple of walnuts in a Moroccan dish and a fading bunch of cornflowers, and perhaps a picture of your grandmother.